Tomoki Hotta

Vice Chancellor

Babel University Professional School of Translation

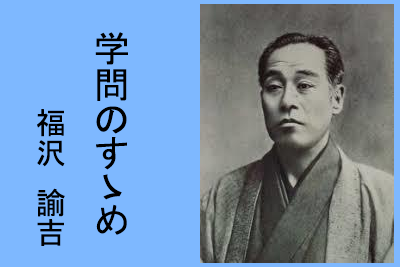

From An Encouragement of Learning

Fukuzawa Yukichi’s wrote this famous work An Encouragement of Learning over a period of five years (1872-76) following the Meiji Restoration. Japan’s population at the time was around 35 million, so at over 3.4 million copies sold An Encouragement of Learning was a phenomenal bestseller. Put these figures in today’s terms with Japan’s population at around 120 million; 12 million copies of this book would have been sold!

Japan at the time was in the midst of significant change following the Meiji Restoration, a period where Japan was forced to end its closed country policy and dive headlong into a full-scale global society. Indeed, this was a highly turbulent period, where revolutions in society and the State were imminent.

An Encouragement of Learning served as a guidebook for forging through this new era, and scores of Japanese people hungrily read its pages as they looked for answers in uncertain times.

An Encouragement of Learning didn’t simply extol the supremacy of ability for the individual, but rather explained an individual’s function and role in society, teaching that when the individual became independent, it was possible for the State to prosper. Fukuzawa used the term dokuritsujison (independence and self-respect) to describe these ideas.

Looking at the issues Japan faces today, many point out that the difficult problems Japan faced during and following the Meiji Restoration interestingly coincide with Japan’s problems today.

• The wave of globalization is surging in, with Japan frantically scrambling about with a lack of clear autonomy.

• Neighboring countries are hinting at unwarranted intentions of aggression.

• Japan is on the verge of bankruptcy because of its long-term deficit.

• Japan favors corporations at the expense of its people.

• The social system is collapsing, with delayed structural reforms continuing along at a snail’s pace.

In light of these conditions, it’s clear that now is the time for Japan to have a definite vision for the next age, just like Fukuzawa pointed out in his time. That vision is one where people do not rely on the State but are rather aware of what they can do individually.

Fukuzawa called for “an encouragement of learning” during a time of great change in Japan.

It’s here that I’d like to propose a new point of view – one that shifts our awareness of the times to focus on the useful and practical study of translation. One could call this point of view “an encouragement of translation.” Or, perhaps its better phrased as “an encouragement for broadcasting Japan,” a phrase which hints at Japan’s new role in the world.

As the world becomes increasingly borderless, “translation” becomes an essential methodology for utilizing various languages, sharing information, and harmoniously bringing about mutual development. Japan has long been known as a translation-intensive nation, but despite Japan’s history of translation use, there’s no denying that current national policies place far too little value on translation. By taking advantage of the refined communication style that characterizes Japan, Japan can use translation to translate from and into various languages, and once again become a “translation-intensive nation.” This will enable Japan to become a bridge between the East and West, North and South. Translation will also help Japan to eradicate disparities in information between Japan and the world and contribute globally. These ideas are not far-fetched dreams, but realistic and attainable goals.

BUPST was founded in 2000 to accomplish those goals. Since its founding, BUPST hasn’t been content simply to define how higher education in translation should be but also strives to construct “translation nationalism” as national level policy.

Since the Meiji Restoration, Fukuzawa Yukichi and other members of the Enlightenment Movement in Japan – such as Nishi Amane and Nakae Chomin – quickly brought in Western culture and ideas Western into Japan with a so-called “Japanese spirit applied to Western learning” to modernize Japan. In other words, Japan used translation to import into Japan ideas from advanced Western cultures and civilizations at the time. That’s why Japan is commonly called a “translation-intensive nation.”

During the six and seventh centuries when Japan brought in Chinese culture, it matched classical Japanese (Yamato language) with traditional Chinese to create its own unique translated words. Since the Meiji Restoration Japan has created translated words for Western humanities and social sciences to express abstract concepts previously nonexistent in Japanese society. Words such as society, justice, truth, reason, conscience, subjectivity, structure, dialectic, alienation, existence, and crisis are some examples. Almost anyone would agree that such translated words are now freely used by the Japanese.

While translation once held a prominent place in Japanese society, it’s almost appalling to how little value translation is given in Japanese society today.

Of course, the general public reads books translated into Japanese, and the government/corporations set aside large sums for translation. In addition, the Japanese can freely enjoy world classics such as works from Dostoevsky and Thomas Mann. Looking at the future, even though national borders will become increasingly unimportant, there will still be a large volume of translation.

Some say that the amount of money corporations will spend on outsourcing translation will total around 200 billion Japanese Yen (JPY). Add to this translation for anime, comics, and other related industries, and the total spent on translation could reach one trillion JPY.

If that’s the case, the role of translation for Japan’s business trading and cultural development – not just in the past but now and into the future – is mind-boggling. Recognizing just how large a role translation plays, it’s time to reconsider translation’s role in Japan today, switching from translation focused on receiving information to translation that transmits information. Such translation creates opportunities for fostering harmony between the West and East.

So, what if the great translator Fukuzawa Yukichi was alive today?

He probably would have been frank in stating the following:

If an individual becomes independent, a household achieves independence as well, as does a nation. Let each one of us view the world with this in mind, considering the role Japan should play in the world. No one can deny the fact that the Japanese possess both profound and refined communication skills, which can foster global harmony. Therefore, let us be ambitious and take action! One cannot question the success or failure of that never tried!

In addition, when asked about how translators should be today, Fukuzawa Yukichi would have likely stated the following:

You translators who are active in the field! Use your eyes and senses to discover all that is lovely and incorporate what you find into your culture. Also, search your own culture for ideas you should share with the world! Then stand between the East and West and devote yourself to achieving harmony among Eastern and Western cultures and civilizations!

In the next article, we’ll look at ideas from Itsuo Kohama’s book Fukuzawa Yukichi and Japan’s Graceful Spirit, published in May of this year, to consider what we should learn from Fukuzawa Yukichi, and what his true – yet often misunderstood – nature was. In doing so, we’ll discover that Fukuzawa Yukichi’s ideas are not outdated but relevant for us today.